|

|

|

http://www.varalaaru.com A Monthly Web Magazine for South Asian History [187 Issues] [1839 Articles] |

|

|

|

http://www.varalaaru.com A Monthly Web Magazine for South Asian History [187 Issues] [1839 Articles] |

|

Issue No. 184

இதழ் 184 [ மே 2025 ]

இந்த இதழில்.. In this Issue..

|

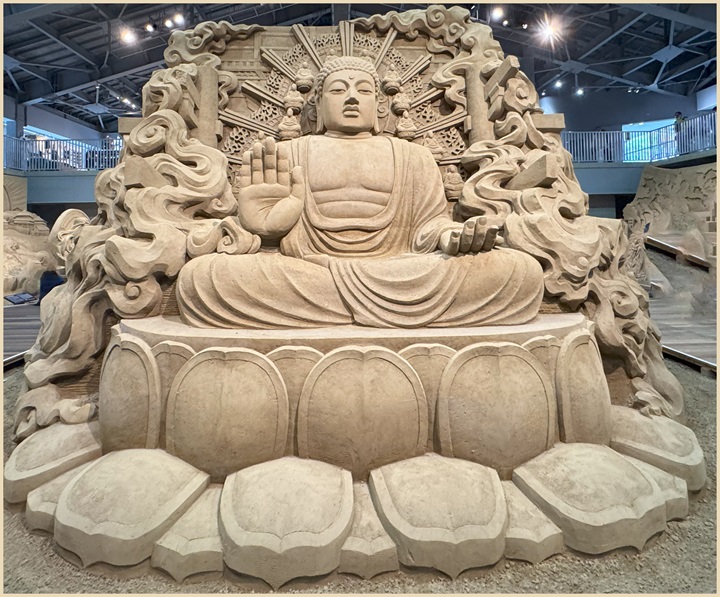

Introduction Introduced to Japan through Korea during the 6th century CE, Buddhism rapidly became an integral component of the nation's cultural and spiritual fabric, weaving itself into the very heart of Japanese life and thought. The newly introduced faith not only harmoniously complemented the existing indigenous Shinto traditions but also provided a robust framework for achieving political legitimacy, ultimately contributing to the establishment of a society characterized by its structured and hierarchical nature. Throughout its history in Japan, Buddhism has profoundly impacted many facets of Japanese society, not just religious beliefs but also leaving an indelible mark on educational systems, literacy levels, artistic expression, and the very framework of its political systems.  Arrival and Early Support Historians generally accept either 538 or 552 CE as the year Buddhism was introduced to Japan, an event widely attributed to the influence and agency of the Korean kingdom of Baekje. Tracing their lineage back to Korea, the influential Soga clan emerged as the strongest and most dedicated champions of this new faith. The impact of their influence was substantial, allowing Buddhism to not only enter but also to become firmly established within the circles of power in the Japanese court. Although clans loyal to the Shinto religion, such as the Monobe and Nakatomi clans, resisted the spread of Buddhism, the religion eventually received official approval during the short reign of Emperor Yomei, which lasted from 585 to 587 CE. Subsequent to its endorsement, Japan embarked upon a significant undertaking: the dispatch of numerous monks, scholars, and students to China to engage in the profound and detailed study of Buddhist philosophy. The emissaries' return was marked by the introduction of a vast collection of religious texts, artistic styles, and accumulated knowledge, all of which served to substantially enrich the cultural tapestry of Japan. Prince Shotoku and Buddhist Consolidation In the development of Buddhism in Japan, Prince Shotoku (574–622 CE) stands out as a truly crucial and pivotal historical figure whose contributions to the religion's establishment are undeniable. From 594 CE onward, his regency was marked by a unique blend of Buddhist and Confucian principles, a strategy he employed to significantly enhance the state's authority and influence. The year 604 CE marked the creation of the Seventeen Article Constitution by him; this document served as a moral code, placing significant emphasis on societal harmony and the reverence of the Three Treasures, namely, the Buddha, the Dharma, which embodies the Law, and the Sangha, the monastic community. The construction of many Buddhist temples and monasteries, including the renowned Shitennoji and Horyuji, along with the production of significant religious imagery and sutra commentaries all occurred during Shotoku's era, thereby establishing the core architectural and intellectual foundations of Japanese Buddhism. Imperial Patronage and Expansion Subsequent rulers, in the line of succession, continued to provide their support to the Buddhist faith. The reigns of Emperors Temmu (672–686) and Jito (686–697) witnessed a considerable expansion in temple building projects; furthermore, these emperors strategically employed monasteries as secure repositories for essential government documents. The ambitious undertaking of constructing a temple in every province was initiated by Emperor Shomu, whose reign spanned from 724 to 749, and this massive project found its culmination in the grand Todaiji Temple in Nara, which was completed in the year 752 CE. The swift growth of the temple's wealth and power, however, led to considerable and growing concerns among the populace. The legal codes of the Taiho Ritsuryo (702) and Yoro Ritsuryo (757) implemented strict regulations upon the actions and authority of monks, explicitly prohibiting them from acquiring property, actively spreading their religious beliefs, or participating in commercial activities. In spite of attempts to prevent them, exploitative actions by monastic orders, such as taking land and using usury, persisted. Coexistence with Shinto Instead of supplanting the native beliefs of Japan, Buddhism accommodated itself to Shinto, the indigenous animistic faith of the country, resulting in a long period of peaceful coexistence between the two belief systems. In contrast to Shinto's focus on the earthly world and its natural elements, Buddhism offered a framework for understanding the afterlife, resulting in a synergistic and complementary religious system. The blending of Shinto and Buddhist beliefs resulted in the creation of Ryobu Shinto, a system in which Shinto gods and goddesses were reinterpreted as different forms of Buddhist deities, such as the prominent example of Amaterasu being viewed as an incarnation of the central Buddhist divinity Dainichi Nyorai.  The coexistence of temples and shrines at the same sites was a common occurrence, frequently resulting in the unique phenomenon of priests from one religion managing the affairs of another's religious institutions. Even with the imperial decree of 764 CE giving Buddhism a position of dominance, the population of Japan, by and large, persevered in their devotion to the indigenous Shinto faith and its associated rituals. In spite of potential challenges or obstacles, Buddhist death rituals and cremation practices ultimately gained broad acceptance and became prevalent throughout all social classes. Societal Role of Buddhist Monasteries The monasteries, through the acquisition of large land tracts and the benefit of tax exemptions, rose to become powerful entities in both the economic and political spheres. In order to safeguard their own self-interests, some people even resorted to maintaining private armies. Emperor Kammu, who ruled from 781 to 806, relocated the capital from Nara to Heian-kyo (Kyoto) due to growing anxieties regarding the undue political interference of Buddhist monasteries. In addition to their religious roles, monasteries functioned as vital community hubs, providing essential services such as education, preserving knowledge through the maintenance of libraries, alleviating hunger through food distribution, and improving infrastructure through construction projects. Imperial authorities, however, sometimes intervened to limit the monasteries' power, particularly in situations where the monasteries' financial contributions exceeded the emperor's ability to manage them. Major Figures and Sects The journeys of Japanese monks to China introduced them to a wide array of philosophical and religious ideas, significantly impacting the development of early Japanese Buddhism and leading to the creation of various sects such as Kusha, Sanron, Ritsu, Jojitsu, Kegon, and Hosso. Kukai and Shingon Buddhism The renowned scholar and monk Kukai (774–835 CE), later known as Kobo Daishi, undertook a significant period of study in China between 804 and 806 CE, focusing his efforts on the intricacies of Mikkyo, the esoteric Buddhist tradition. He came back and shared his knowledge of Shingon Buddhism, which centers on the concept of Mahavairocana (Dainichi), a Buddha who represents the cosmos. He highlighted the path to enlightenment in this life as achievable through the practices of mudras, intricate hand gestures, the recitation of mantras, or sacred chants, and the contemplation of mandalas, complex and symbolic visual diagrams. On Mount Koya, Kukai, a highly influential figure, founded a significant monastic center and, demonstrating his scholarly dedication, compiled the "Shorai Mokuroku," a catalog of the many imported sutras. In the year 823 CE, Emperor Saga gave his official recognition to the Shingon school of Buddhism. Saicho and Tendai Buddhism The Tendai sect was founded by Saicho (767–822 CE), a figure who is now honored with the posthumous title Dengyo Daishi, after his studies in China were completed. In 788 CE, near Kyoto, on the slopes of Mount Hiei, he founded the renowned Enryakuji Temple, a significant establishment in the region. By emphasizing esoteric rituals, he presented them as the most efficient way to achieve enlightenment, all the while blending elements of Buddhist philosophy. Because Saicho’s Tendai Buddhism gained the favor of the imperial court, it became the bedrock upon which subsequent schools of Buddhist thought, such as the Pure Land and Nichiren sects, were built and flourished. Legacy and Later Developments Throughout the era of the Middle Ages, the Tendai and Shingon schools of Buddhism served as the origins for the development of many new and distinct sects. The prominent schools of thought included Pure Land (Jodo), which highlights the significance of faith in the Amida Buddha as the primary path to enlightenment. With a central focus on the Lotus Sutra, Nichiren Buddhism is distinguished by its emphasis on social reform and its active engagement in the betterment of society. Zen Buddhism is a school of Mahayana Buddhism that emphasizes the practice of meditation and the direct experience of enlightenment, foregoing scholarly study and hierarchical structures in favor of experiential learning. The fifteenth century witnessed a resurgence of Shinto in Japan; however, Buddhism, deeply embedded within Japanese cultural life since its introduction, maintained its powerful influence, a legacy still readily apparent in contemporary Japanese society. Conclusion In Japan, Buddhism has undergone a vibrant and evolving journey, dynamically adapting to the cultural landscape, synthesizing with indigenous spiritual traditions, and resulting in a rich tapestry of spiritual experiences. Tracing its path from its foreign roots to its significant impact on the development of Japanese politics, art, education, and philosophy, the enduring presence of Buddhism has undeniably established itself as a fundamental pillar of Japanese civilization. Not only did it coexist with native beliefs, but it also inspired reformers, produced monumental architecture, and gave rise to some of the most profound spiritual thought ever known in East Asia. |

சிறப்பிதழ்கள் Special Issues

புகைப்படத் தொகுப்பு Photo Gallery

|

| (C) 2004, varalaaru.com. All articles are copyrighted to respective authors. Unauthorized reproduction of any article, image or audio/video contents published here, without the prior approval of the authors or varalaaru.com are strictly prohibited. | ||