|

|

|

http://www.varalaaru.com A Monthly Web Magazine for South Asian History [187 Issues] [1839 Articles] |

|

|

|

http://www.varalaaru.com A Monthly Web Magazine for South Asian History [187 Issues] [1839 Articles] |

|

Issue No. 49

இதழ் 49 [ ஜூலை 16 - ஆகஸ்ட் 17, 2008 ]

இந்த இதழில்.. In this Issue..

|

திரு. ஐராவதம் மகாதேவன் அவர்களின் Felicitation Volume இன் 'English Articles' பகுதியில் வெளிவரும் கட்டுரைகளின் முன்னோட்டம்.

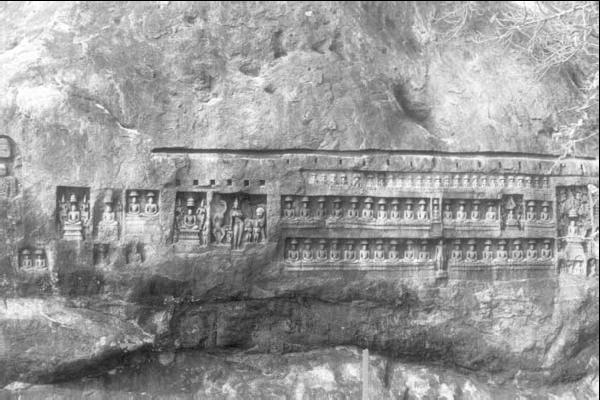

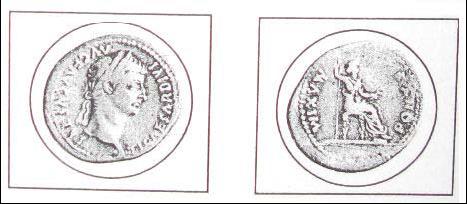

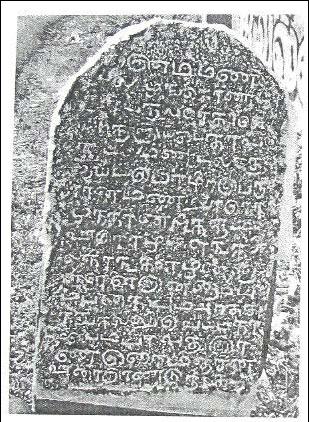

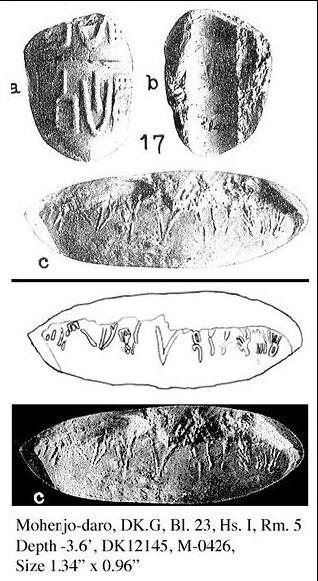

Title : From natural caverns to rock-cut and structural temples: The changing context of Jain religious tradition in TamilNadu Author : Champakalakshmi, R. Introduction Jainism, by its very nature as a rigorous and strictly disciplined religion in its origin, has remained less visible in power and authority structures of India, with the exception of some regional and prosperous community based support to its doctrines and philosophy , religious and monastic institutions. The Tamil region has been one of those few regions which have preserved evidence of its spread, influence and capacity to draw a fair number of lay followers in the pre- modern times. Much of its early history is shrouded in legends and traditional lore, which associate its spread in peninsular India, especially the Karnataka and Tamil regions, with the migration of a large Jain community under the Srutakevali Bhadrabahu and his royal disciple1 identified with Candragupta Maurya, predating the spread of Buddhism under Asoka. The migration took the Jains first to Karnataka, where the centre of its early establishment is known to be Sravana Belgola. This centre abounds in Jain inscriptions from about the 5th-6th centuries AD and temples from the 8th-9th centuries AD and continues to be the hub of all Jain activities, especially the evolution of various sects of the Jains in the early period, under the two major branches the Svetambara and Digambara, the latter being more conspicuous in South India. From Karnataka, one Visakhacarya is believed to have led the Jains into the Tamil country i.e. the Cola and Panoya region. Interestingly, no significant Jain inscriptions of the early historical period are available in the peninsular regions other than TamilNadu and Kerala, which together formed the Tamilakam of this period. The earliest Jain inscriptions in Brahma script and Tamil language have been found in this southernmost region and dated to a period from 2nd century BC to 3rd century AD followed by Vattezhuttu inscriptions from the 5th century AD. Tamilakam therefore contains crucial evidence of the spread and influence of Jainism among a sizeable population and patronage from ruling families, traders and craftsmen.  Rock Cut Sculptures of Tirthankaras and Attendant Deities, Kalugumalai (Tirunelveli District), 9th Century AD Indirectly the Tamil Brahmi inscriptions confirm the tradition of the movement of the Jains to the south, the literary evidence of this tradition coming up only from about the 10th century in the B?hat Kathakosa of Harisena (AD 931) and the later Rajavali Kathe and other works2. Hence the rediscovery, correct reading, reinterpretation and dating of the Tamil Brahmi inscriptions by I. Mahadevan (See Appendix- Chart) assume greater importance for the history of the Jains than for the Buddhists whose presence in the Deccan and Andhra regions is more clearly established by Asokan edicts and by monumental Buddhist art and architecture in the post-Mauryan period coinciding with a network of trade routes and commercial centres. The present paper aims at revisiting the early Jain caverns with Tamil Brahmi inscriptions and situating them in their historical context and the trajectory of change in the religious tradition of Jainism in the Tamil region from the early historical (2nd century BC to 3rd century AD) to the early medieval period (6th century to the 13th century AD). The early historical Sangam texts, which are manifestly non- religious in character, refer to many forms of belief and practices relating to folk / tribal traditions and also to what has been generally called the mainstream tradition of the Vedic and Puranic Brahmanism, the counter tradition of Sramanism (Buddhist and Jain) along with the popular forms. 1 S.B.Deo, The History of Jaina Monachism from Inscriptions and Literature, Bulletin of the Deccan College Research Institute, 16 (1-4), 1956, pp.86-88. See Narasimhachar, Epigraphia Carnatica, Vol. II, Introduction, p.36. 2 Narasimhachar, op.cit., pp.37 ff Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : Tutu poems in Tamil poetry Author : Dubyanskiy, Alexander When speaking of the so-called messenger-poems in Indian literature one cannot avoid mentioning Meghaduta by Kalidasa, the most celebrated poem of the genre designated by Indian tradition as duta?or sandesakavya. It is known that Kalidasa's poem generated imitations, the earliest among them, perhaps, Candraduta by Jambukavi (between 8 and 10 cent.). The next one is Dhoyi's Pavanaduta. There are also others?in Sanskrit and manipravalam (a special poetic language, a mixture of Sanskrit and one of Southern languages?Tamil, Malayalam or Telugu), for which Meghaduta was to a certain extent a model12. A natural question arises: if there was a model for Kalidasa's poem, what sources he could rely on. One can point out the story of Nala from Mahabharata where Nala sends a message to Damayanti with a goose which later brings Damayanti's answer to him. Indian tradition, in the opinion of a medieval commentator Mallinatha, names as Kalidasa's source Ramayana, or more exactly the episode of Hanuman's embassy to Lanka [Kale 1979, 12]. No doubt both stories could be a source of inspiration for Kalidasa, but this does not explain, however, the origin of the given poetical form. Anyway, Kalidasa's poem seems to be the earliest known representative of the genre and opens a long list of poems created in India throughout many centuries and in many languages?not only in Sanskrit and Prakrit but in Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, Kannara, Bengali and others. We also find sandesa poems in Sri Lanka written in Singhala language. The poems considerably differ from each other in their contents. There are, first of all, love poems, the best example is again Kalidasa's creation (a yaksha separated from his wife sends a message with a cloud); let us mention also Kokilasandesam by Uddandakavi (15 cent.) the hero sends a cuckoo from Kanci to Kerala to his beloved. Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : New lead coins and other inscriptions from Tissamaharama, Sri Lanka Author : Falk, Harry The early phases of coinage in Sri Lanka are devoid of breathtaking examples of workmanship. In the third century BC punch-marked coins were imported and soon after copied locally. Cast copper coins surfaced in Anuradhapura from the 2nd century BC on, according to Sirisoma 1972: 150. Focusing on Tissamaharama in Southern Ceylon, Walburg (1993 and 2001) saw hardly any local coinage, apart from the ubiquitous Lakshmi plaques, "Indo-Roman imitations" and some stray punch-marked coins. So it came as a surprise when a series of lead coins from the citadel area at Tissamaharama, called Akurugoda, was published in Bopearachchi & Wickremasinhe 1999, showing that some sort of coinage in lead with a common sign inventory was produced in this locality much earlier. This publication incorporated my readings of the coin legends, together with a discussion of their linguistic and paleographic features (pp. 51-60), plus readings and discussion of some seals and sealings (pp. 61-64), duly acknowledged in footnote 17 on page 15. This part of the book was again published as Bopearachchi / Falk / Wickremasinhe 2000 without the possibility of including the many additions and corrections that had accrued in the meantime. There were three reactions to this catalogue. J. Lingen (2000) added one new kind, acquired in Colombo, and another specimen already published as E12, showing, however, a readable legend. This latter coin was bought in Goa pointing, possibly, to a wider distribution in antiquity. R. Walburg (2005) did not challenge the readings, but insisted that these sorts of lead coins do not deserve the term "coinage", because they are not issued by the general authority in sufficient quantity. Given the limited regular excavations at the place and the haphazard nature of other coin finds, we have to say that we have no means of judging the magnitude of these editions. A trader in Kataragama, who claims to have sold all the coins contained in this catalogue, speaks of about one thousand lead coins from Akurugoda having crossed his desk. These lead are certainly not very systematic as to their weight (cf. table in Walburg 2005: 371a). Nonetheless, they seem to have served in the exchange of trade goods of some sort, thus showing the main characteristics of coinage: being an intermediary between goods, service and value. As long as the mediation as such is accepted by their users, any series of metal pieces can be called coinage in their own right. In India, such coinage is usually called "guild coinage", regarded as being issued by traders in a certain area. One argument of Walburg against the nature of these coins is extremely irritating. Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : Roman Coins associated with Christian Faith found at Karur and Madurai Author : Krishnamurthy, R. In the Roman Empire the cities and towns had patron Gods. Some of the Emperors performed the role of Chief Priests and sometimes they were defied after death1. The birth and spread of Christianity tested their tolerance limits. Though the Churches of the Christians and their writings were destroyed by them, it continued to grow through periods of persecution and relative calm.2 Constantine the Great is recognized as the first Christian emperor and certain elements of his coinage came inextricably to be associated with the triumphant religion. Karur and Madurai in TamilNadu have yielded some Roman coins which we can associate with Christianity. They are illustrated and described in the following pages. To this day, the most popular coin associated with Christian faith is the 'tribute Penny', a silver denarius of Tiberius (AD 14-37). In those days, there was a decree from Caesar Augustus that the entire world should be taxed (Luke 2:1 ); it is learnt from the Bible that when Christ was asked whether tax should be paid to the Romans or the God, Christ said "show me the tribute money". When they showed the silver denarius of Tiberius to Christ, he seems to have said diplomatically that we should give what is due to the Romans and give to God what is due to God. This dinarius, paid as tribute tax to the Romans in those days, was referred to as Penny in the King James translation of the Bible (1611). If they had called it a denarius, nobody would have understood what it meant. Tribute Penny still remains as a favourite piece among the coin collectors because of their belief that these silver coins were in circulation when Christ was alive. Several coins of this type were found in the Amaravathi river bed and one such coin is described below. Coin No.1  Metal: silver; Wt: 3.450 gms; Dia: 19 mm. Obverse: Portrait of Emperor Tiberius facing right. Reverse: Seated figure of emperor's mother Livia or a personification of pax (peace.)3 Coins with Chi-Rho Symbol This sign, illustrated below, is Chi-Rho, a monogram composed of the name of Christ in Greek.4 1 Mark Dunning, 'First Christian Symbols on Roman imperial Coins', The Celator, Vol 2 Ibid., 3 Kenneth Jacob, Coins and Christianity, Seaby, London, 1985, p.29. 4 Ibid., p.41. Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : Is the Indus script indeed not a writing system? Author : Parpola, Asko Is the Indus script a writing system or not? I represent the traditional view that it is, and more accurately, a logo-syllabic writing system of the Sumerian type. This paper is an enlarged version of the criticism that I presented two years earlier in Tokyo, where it was published soon afterwards (Parpola 2005). What I am criticizing is "The collapse of the Indus script thesis: The myth of a literate Harappan Civilization" by Steve Farmer, Richard Sproat and Michael Witzel /2004), where the authors categorically deny that the Indus script is a speech-encoding writing system. Farmer and his colleagues present ten main points or theses, which according to them prove that the Indus script is not writing: 1. Statistics of Indus sign frequencies & repetitions 2. "Texts" too short to encode messages 3. Too many rare signs, especially "singletons" 4. No sign repetition within any one text 5. "Lost" longer texts (manuscripts) never existed 6. No cursive variant of the script developed, hence no scribes 7. No writing equipment has been found 8. "Script" signs are non-linguistic symbols 9. Writing was known, but it was consciously not adopted 10. This new thesis helps to understand the Indus Civilization better than the writing hypothesis. I shall take these points up for discussion one by one. Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : Texts and Pretexts Author : Parthasarathy, Indira In the early fifties, in one of the public schools in England, the pupils were asked to name the author of 'Hamlet'. Many of the young scholars wrote 'Laurence Olivier'. Apparently, the teacher was not amused but a theatre critic reporting this in a journal wrote, 'it is a reflection of the times; this indicates the triumph of the director over the playwright'. No wonder, therefore, the eminent Polish director Jerzy Grotowskie announced his production of 'Hamlet' as ' Hamlet after Shakespeare', which in other words, means,' Grotowskie's Hamlet inspired by a play of the same name, written by one called William Shakespeare'. A dramatic text is merely a recipe on paper, or perhaps just one of the ingredients, for the creation of an integrated work of staged art. The aesthetic gravity has shifted from the written text toward the production as a whole. No longer it is 'drama' with its overtones of literary art but it is ' the theatre' or 'the stage' referring to the entire activity. A director as an identifiable artist did not exist before the last quarter of the 19th century either in the West or East. Does anyone know who directed 'Hamlet' during the Elizabethan period or the contemporary of Kalidasa who directed 'Shakuntalam'? Only if there had been a director in those days endowed with the kind of theatre sense we associate with him, as of now, these plays would have been reduced to half their size, with the consent of the playwrights, of course, and the loss would not have been much except some glorious lines of immortal poetry! Do we not know that our modern playwrights Samuel Beckett, Jean Anouilh, Jean Genet, Eugene Ionesco and a host of others have only written production scripts and their texts do not draw attention to themselves by their style to evoke an imaginative response but instead, their style is so self-effacing that it gives the impression of merely doing the function of performed plays? The accent is not on words and this willingness of the playwrights to regard the dramatic compositions as pretexts for actors' performances, would be hard to imagine in Sophocles, Shakespeare or Kalidasa... Peter Brook says: 'Anouilh conceives his plays as ballets, as patterns of movement, as pretexts for actors' performances. Unlike so many present-day playwrights who are descendents of a literary school, and whose plays are animated novels, Anouilh is in the tradition of the commedia dell' arte. His plays are recorded improvisations. Like Chopin, he preconceives the accidental and calls it impromptu. He is a poet, but not a poet of words: he is a poet of words '"acted, of scenes-set, of players'- performing". Perhaps, modern playwrights assert their right to compose the whole play for the stage by anticipating every last detail of a production and leave little room for the director to edit what they have written. Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : An Akkadian Translator of the Meluhhan Language: Some Implications for the Indus Writing System Author : Possehl, Gregory L. Introduction Some time ago I published a short paper on an Akkadian gentleman who claimed to be a translator, and/or and interpreter of the Meluhhan language (Figure 1 The Shu-ilishu cylinder seal), Meluhha being the Akkadian name for the Indus Civilization (Possehl 2006; for the location of Meluhha see Possehl 1996). It will be recalled that the founder of the Akkadian dynasty, Sargon the Great (c. 2334-2279 BC), boasted that: He moored The ships of Meluhha, the ships of Magan, the ships of Dilmun at the quay of Akkad. (translated by Gianni Marchesi, 2007 personal communication).  Figure 1 - The Shu-ilishu cylinder seal The translators' name was Shu-ilishu, and his personal cylinder seal was a part of the Collection De Clercq, Catalogue methodique and raisonnee, published in Paris in 1888. The "Collection De Clercq" was gathered together in the 19th century by a wealthy man. It seems to be made up of objects purchased from dealers, and there is little if any provenience data on the materials there. We do not know where Shuilishu's cylinder came from but today the cylinder is in the Department des Antiquities Orientales at the Musee du Louvre, Paris. Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : Archaeological Investigations at Thandikudi Authors : Rajan, K., Athiyaman, N., Yathees Kumar, V.P. & Saranya, M. Introduction Kodaikanal, located amidst Upper and Lower Palani hills, has been a popular hill resort from the British times. Pleasant Climate, tranquil and serene ambience of Kodaikanal triggered the settling of , British administrators and Christian Missionaries in and around Kodaikanal at the beginning of the 20th century. These settlers were the first to record the archaeological wealth of this region in the pre-Independence era. As far as the antiquity of Kodaikanal region is concerned, the earliest human settlement goes back to pre-Iron Age times. This region was associated with a Sangam Age chieftain Kodaiporunan (Purananuru 205). Peruntalaisattanar, a Sangam poet, narrated that the chieftain had performed velvi,suggesting that the brahmanical influence on this region as early as Sangam Age. The archaeological sites of this region is placed on the archaeological map through the works of A.V.Rosner S.J., Rev.Heras, S.J., Anglade and Aiyyappan as early as in the early part of the 20th century. S.J.Hosten first reported the Iron Age burial at Parappar falls near Senbaganur. Further, Anglade reported stone circles entombing cist burials in the places like at Palamalai, Perumalmalai, Munjikal, Senbaganur and Mulaiyur ridge in 1928. He reported these cist burials as buried dolmens (Anglade and Newton 1928:12). In 1936, A.V.Rosner S.J., excavated a cist at Tevankarai on the slopes of Perumalmalai. In 1939, Rev.S.J.Heras excavated a cist at Mulaiyar. Quite interestingly all the above-mentioned sites have yielded dolmens in association with cist burials. Father Anglade and Newton have described the dolmens of the Palani Hills in their paper, which was published in Memoir No. 36 of the Archaeological Survey of India (Anglade and Newton 1928:118). Therefore, the credit of bringing Iron Age monuments like dolmens, stone circles and urn burials of Kodaikanal region to the academic world goes to Anglade. He used the traditional route from Palani to reach Kodaikanal. He brought to light the groups of dolmens at Kamanur, Pachchalur, Tittaikudi and on the ridge south of the Mulaiyar.He found dolmens close to Kodaikanal on the slopes of Machchur and Perumal hills in the Vilpatti valley and at Pallangi and Palamalai. Many of these, however, are little more than ruins or heaps of stones.sometimes the remains found are just enough to show the existence in former times. Anglade carried out excavations at Perumalmalai, Senbaganur, Tevankarai valley and Mulaiyar ridge. His findings are currently displayed in Senbaganur museum. His pathbreaking work brought the attention of the scholars like Aiyyappan to Kodaikanal. Aiyyappan, a renowned anthropologist, in 1940 (Aiyyappan 1940-4 l:373-379) excavated two cists at Vilpatti. It yielded a number of black and red ware potteries, which were displayed in Madras Government Museum. Allchin had made a fair attempt to give a date to these sepulchral monuments by comparing these potteries with other Iron Age potteries. M.Saranya, a research scholar, took an extensive survey and extended the frontiers of research by locating many such monuments, irrespective of the inaccessible terrain (Saranya 2003). Some of the sites that need attention are Kathavumalai, Kottaikal-teri, Idunja-kuli, Perunkanal, Kumarikundu, and Sankarpettu. The special features of Iron Age burials are discussed elaborately by taking previous works into consideration To understand their distributional pattern, the Iron Age monuments of this region are compared with the monuments of the plains.  Fig. : Thandikudi inscription of Kulasekhara Pandya Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : Recent discoveries near Mamallapuram Author : Rajavelu, S. Mamallapuram popularly called Mahabalipuram is placed in the Indian artistic annals for its magnificent monoliths and rock cut caves with beautiful sculptures both religious and secular that attracts the scholars as well as art historians and the common folk of the world. Some scholars identify this city as Nir peyarru, the famous port referred to in the Perumbanarruppadai, the Sangam age classic1. Quite a number of Roman coins and other artifacts collected from here testify its antiquity to the hoary past. Recently the author discovered an interesting inscription at Saluvan Kuppam situated five kms. north of Mamallapuram that mentioned a temple for God Subrahmanya, which paved the way for an explorative research and the discovery of a brick temple through excavation.  Fig : Saluvankuppam Murugan Temple - General View Two Pallava monuments namely Atiranachanda cave temple and the Yali Mandapa are located on the eastern side of Saluvan kuppam. Very near to these monuments about 100 meters north, there is a small rock 80 Perumpanarruppadai, lines 320-350 bearing the inscriptions of Parantaka Chola, Rastrakuta King Krishna III and Kulottunga Chola III. The inscription of Kulottunga III was published2 but the remaining two inscriptions were unnoticed. The inscription of Kulottunga III mentions about a temple for Subrahmanya in the vicinity of the place and the newly discovered Rastrakuta inscription supports the statement. 1 Perumpanarruppadai, lines 320-350 2 S.I.I., Vol. IV., No, 381 Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : Chandesa in art and literature Author : Santhalingam, C. It is a custom among the devotees of Lord Shiva, to record their attendance in the temple, before a particular deity - by clapping their hands. Many do not know the reason for such a clap. Some even believe that the deity is deaf and therefore a heavy clap with the hand may actually make their attendance audible to the deity. The actual significance of this act is different. The deity is infact one of the eight standard Parivara Devatas of Lord Siva and he is considered as the steward of the celestial household. His name is Chandesa or Chandeswara. All transactions of a Saivite temple ? financial or otherwise ? are supposed to be done in the name of this guardian deity only. When devotees visit the temple, they expected to show their empty hands to Chandesa ? before stepping out. This is to prove that they are not taking anything away from the temple. This seems to have resulted in the above mentioned practice and gradually the actual significance of the act was lost. Who is this deity by name Chandesa and how did he attain such a significant position in Siva temples? The answer to this lies in an interesting episode in Periya Puranam, a religious literature ascribed to 12th Century AD. Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : Finger rings from Karur - Some reflections Author : Shanmugam, P. Finger ring is a personal ornament worn by an individual. People of all ages and irrespective of their gender wear it on their fingers. Some are very fond of wearing finger rings and on occasion sport with rings in all their fingers. There seems to be no economic barrier in wearing finger rings as both the rich and poor adorn themselves with different kinds of rings. Among the social groups, the economically higher and socially powerful individuals used to wear costly and highly ornate varieties compared to the poor who choose to adorn with crude types of finger rings. The size and shapes are varied and according to the taste of an individual one can choose his own. Rings were mostly made of gold and sometimes in other lesser materials like silver and copper. Rings are patterned with some designs and in some the designs and figures are executed with precious stones like gems, diamonds, pearls and corals. Some finger rings are inscribed with the name of an individual, suggesting ownership. Though, finger ring was initially considered as a simple and personal ornament, over a period of time it became a symbol for many social, economic and even administrative functions. In some regions, wearing a finger ring was considered as indicative of one's social status. When the state structure developed in some political regions, a finger ring with official markings was recognized as a symbol of administrative power. In India, there is no precise evidence to suggest the antiquity of the custom of wearing finger rings. However, some of the legends in early Indian literature suggest the popularity of this custom among the common folk. In the famous story of Sakuntala, the finger ring was handed over to her as a symbol of marriage with king Dushyantha and later became an important evidence for identifying her husband. The story provides a clear idea that the custom of wearing finger rings and its acceptance among the people. There is another reference from Mudrarakshasa, about the utility of a finger ring by a Minister of high rank. The work clearly demonstrates that finger ring of a Minister could be used as an important instrument of identity and also received respect and recognition among all the officials of the government. We have no idea about the antiquity of the custom of wearing finger rings among the people in the Tamil country. However the custom could be traced to the early historical period. In some of the megalithic burials in TamilNadu, the dead were buried with their finger rings. In Kodumanal, in one of the burials (Megalith-VII) were found two finger rings of gold. They are of solid spiral rings weighing about 2 gm. having a diameter of 1.6 cm and a thickness of 1 mm. From the small size we can infer that these rings belonged to a child. Since they were found inside a burial, we may also suggest that with the dead their personal ornaments were also placed. Finger rings were discovered at other sites also. Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : Raya Asoko from Kanaganahalli: Some thoughts1 Author : Thapar, Romila A small piece of information has surfaced from the recent excavation by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) of the stupa at Kanaganahalli. This raises some interesting questions concerning the perception which people at that time had of their recent past and the articulation of this perception, as well as its relationship to other perceptions from approximately contemporary times. My attempt here is to suggest the direction in which some enquiries can be made. The site of Kanaganahalli lies on the left bank of the river Bhima five miles from the previously excavated site of Sannati in the Gulbarga District of Karnataka. Sannati was a large urban settlement with a fortified citadel dated to the early historical period. It has three stupa mounds in its vicinity2. The stone slab for the pi?ha, pedestal, for an image in the Candralamba temple in its neighbourhood was found to have partial texts of the Major Rock Edicts XII and XIV and the Separate Edicts I and II of Asoka inscribed in Asokan brahmi3. The slab was damaged by the cutting out of a section in the middle to hold the tenon at the base of the image. Sannati was therefore an important site in the Mauryan period. This is also indicated by the presence of Northern Black Polished Ware and some punch-marked coins from the Mauryan levels at the site. As a Buddhist centre the geographical links of Kanaganahalli would have been with the stupas of central India and the Deccan, with the many Buddhist sites along the east coast, and westwards with the cave monasteries of the Western Ghats. Buddhist sites are located seriatim down the east coast with a striking cluster in the Krishna delta around Amaravati and further upstream. The Bhima valley was also a route going towards the Western Ghats with their multiple passes down to the coast and the location of Buddhist sites at virtually each one. Andhra would have had extensive contacts through maritime trade both across the Arabian Sea and along the east coast. The location of Kanaganahalli would probably have been along the route from the north going south perhaps the much-mentioned daksinapatha. This would have continued to the Raichur Doab and the Krishna valley with its cluster of Asokan edicts suggesting an area known to Mauryan administration. Votive inscriptions from the Sannati stupa indicate the presence of what seem to be two Yavana women and one identified as Sinhala122. Roman and Satavahana coins point to the importance of this area in post-Mauryan times as well. 1 I would like to thank the Archaeological Survey of India and particularly Mr. K.P. Poonacha and Mr. R.S. Fonia for providing the photographs included in this paper, and especially those from the Kanaganahalli excavations, and for the discussions that I had with Mr. Poonacha who excavated the site. I would also like to thank Professor Michael Meister for discussions on the Kanaganahalli panels. 2 M.S.Nagaraja Rao, "Brahmi Inscriptions and their bearing on the Great Stupa at Sannati," in F.M.Asher and G.S.Ghai (eds.), Indian Epigraphy, New Delhi 1985, pp. 41-45. J.Howell, "Note on the Society's Excavation at Sannathi, Gulbarga District, Karnataka, India," South Asian Studies, 1989, 5, pp. 159-63. 3 K.V.Ramesh, "The Asokan Inscriptions at Sannati," Indian Historical Review, 1987-88, XIV, 1-2, pp. 36-42; K.R.Norman, "Asokan Inscriptions from Sannati," South Asian Studies, 1991, 7, pp. 101-10. Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : The Pandya rule at the beginning of ancient Lankan history Author : Veluppillai, Alvappillai How does one write the history of a country? If one ethnic religious community in a country has a record of its past, it should be utilized as an important source. How the other community or communities which live in the same country view that record is also important to assess critically the historical value of that past record. Archaeological explorations and epigraphy are much more important than past written chronicles, composed in the form of poems, referring to events which happened many centuries earlier. Foreign notices also provide an important source, which could help in reconstructing a balanced view of history of the country. It is also important to study the history and developments in the region, the geographical location of the country, its position on trade routes, etc. Does Sri Lanka have a history in that sense? I am amused when some Sinhala chauvinists say that liberals and progressives advocating the restructuring of the history of multiethnic and multicultural Lanka are wrong because they don't know the history of Lanka. According to the understanding of the author of this article (referred to as 'this author' subsequently), it is the Sinhala chauvinists who have been misled by their ancient chronicle, a biased and distorted account of the history of this island. The availability of the Mahavamsa, a Pali chronicle ascribed to the authorship of Mahanama, a Buddhist monk, has been a blessing as well as a curse. It has preserved some useful information, which are important not only for Sri Lanka but also for South Asia. But it has bred a mindset which promotes chauvinism among the Sinhala Buddhists of Sri Lanka and which stands in the way of reaching of reaching any amicable and just solution to the national question in Sri Lanka. There is still no balanced and well-researched history of ancient Lanka, partly because Sinhala Buddhist scholars find it difficult to get over the Mahavamsa mindset, partly because findings from ancient South Indian sources have not been correlated and integrated, and partly because archaeology and epigraphy of ancient Lanka have not been given primacy as sources but have been interpreted in the light of the Mahavamsa, a chronicle written with a very narrow vision in about the fifth century ACE, encompassing the story of about one thousand years. Rest in the felicitation volume. Title : The Classification of Indus Texts Author : Wells, Bryan Methodology The inspiration for this research approach comes from earlier research efforts, most notably Mahadevan (1977) and later Parpolla (1994). The goal of this research is to define patterns of sign distributions that can be compared to morphological and syntactic rules in candidate languages. The identification of THE Indus language is the next best step in the eventual decipherment of the Indus script. The results of my dissertation research points to a root language that uses infixing and prefixing, as well as agglutination. I will leave it to the Proto Linguists to argue the fine points of these results. It has been proposed (I think correctly) that THE Indus language was really several languages (Witzel 1999). The problem arises in assessing the relatedness of these languages and in accounting for changes over time. The main obstacle to decipherment is the limited nature of the corpus of Indus texts. Further, each researcher has their own sign list (including me). The results of structural analysis depend heavily on the sign list and these two circumstances lead to distinctly different results. What follows is a brief overview of the results of my structural analysis (Wells 2006). My methodology follows Mahadevan (1970, 1977, 1981, 1982 and 1986). The Data The analyses in this paper are based on a database compiled in 2004-05, mainly using site reposts and the CISI. Richard Meadow allowed me access to the unpublished HARP material, which added greatly to the corpus of texts and to the sign list. The database describes 3831 texts with 17, 420 signs (mean length = 4.55 signs). Of these inscriptions 2359 are complete (61.6%), containing 11, 615 signs (mean length = 4.9 signs). It is these complete inscriptions that form the heart of the following analysis. It is important to realize the restrictions that the corpus places on analysis. We are likely looking at only a fraction of all Indus writing. We know this from a single example found by MacKay (1938) in DK.G section at Mohenjo-daro. The tag (sealing) picked up the relief of a text in thick ink or paint. From this case we know "perishable texts" exist in the form of painting on wooden dowels. What we do not know is what other types of perishable texts existed and hoe they might have differed from the know texts.  Rest in the felicitation volume. this is txt file� |

சிறப்பிதழ்கள் Special Issues

புகைப்படத் தொகுப்பு Photo Gallery

|

| (C) 2004, varalaaru.com. All articles are copyrighted to respective authors. Unauthorized reproduction of any article, image or audio/video contents published here, without the prior approval of the authors or varalaaru.com are strictly prohibited. | ||